Bear Creek at Ponderosa Way

The Watershed at a Glance

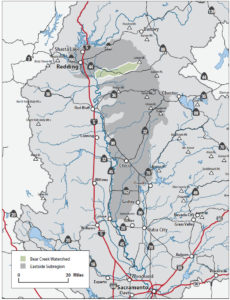

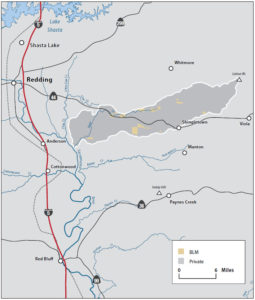

The Bear Creek Watershed lies on the east side of the Sacramento River in Shasta County (for the purposes of this discussion, it also includes the Ash Creek watershed, a separate but adjacent Sacramento River tributary). It is bordered on the north by Cow Creek and on the south by Battle Creek. Land ownership in the watershed is primarily private, and land use is dominated by commercial timber production in the upper elevations and cattle ranching operations in the mid and lower watershed area. Bear Creek provides important spawning and rearing habitat for fall-run salmon and steelhead that migrate from the Sacramento River. The watershed is sparsely populated, and residents place a high value on open space preservation and a rural lifestyle.

Hydrology

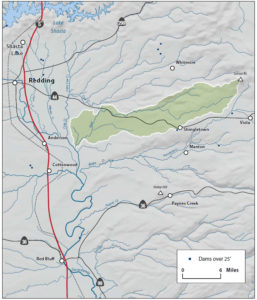

Based on streamflow gaging conducted by USGS during the period 1960 to 1967, the average annual flow for Bear Creek is 82 cfs. Peak storm flow can reach 5,000 cfs, and in low-rainfall years, lower Bear Creek becomes dry in the late summer season. Irrigation diversions and groundwater pumping contribute to the summer low-flow conditions. Shallow groundwater, in the form of springs and seeps, plays an important role in sustaining surface flow in Bear Creek and its many smaller tributaries. Unlike Cow Creek, water rights in Bear Creek watershed are not adjudicated; however, there are 56 appropriative water right holders that divert water for domestic use, irrigation, stock watering, power generation, and recreation.

Water Quality

No comprehensive water quality study has been done in the watershed; however, both Central Valley RWQCB and DFG have conducted limited monitoring. Water temperature is the principal issue of concern, given its importance to resident coldwater species and migratory salmon and steelhead. In general, water temperatures in the upper watershed are supportive year-round for coldwater species. At lower elevations, summer temperatures exceed tolerance levels for these species, partially because of natural climate conditions and partly because of water diversions and low streamflow. Monitoring also has shown that fecal coliform bacteria concentrations occasionally exceed standards set for protection of contact recreation. Likely sources are domestic livestock and wildlife.

Vegetation

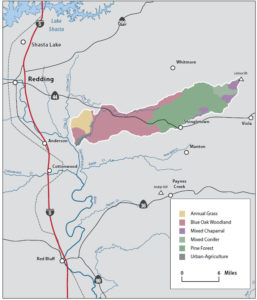

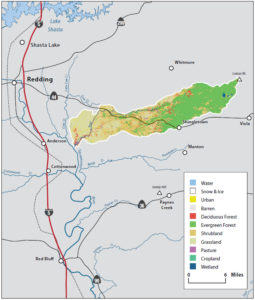

Since the arrival of the first European Americans in the early 1800s, vegetation in the Bear Creek Watershed has been shaped and modified by fire suppression policy, timber harvest practices, livestock grazing, and introduction of nonnative plant species. Dominant vegetation communities are mixed conifer, ponderosa pine, blue oak woodland, and annual grassland. Wet meadows and riparian plant species are common throughout the watershed. Nonnative, noxious weeds common in the watershed are knapweed, Scotch broom, and yellow star-thistle. As in many other watersheds, aggressive fire suppression efforts over the past 100 years have resulted in an accumulation of fuels on the forest floor that pose a high fire hazard to the local residents.

Fish and Wildlife

Chinook salmon and steelhead are known to occur in the Bear Creek Watershed. Of the different runs of salmon that spawn in the Upper Sacramento River and tributaries, only fall-run Chinook salmon return in consistent numbers to spawn in Bear Creek. Estimated (DFG) spawning runs in Bear Creek between 1949 and 2002 ranged from fewer than 10 fish up to 500. Counts in recent years have been very low, reflecting the overall decline in Sacramento River fall-run Chinook salmon. Anadromous fish restoration efforts in Bear Creek will target screening on diversions, increasing instream flows, and general habitat improvement work. State and federal agencies have estimated that potential runs in Bear Creek would be in the range of 1,000 fish. Resident rainbow trout are common throughout the upper watershed and provide an important sport fishery for local residents. Nonnative, warmwater species (e.g., bass, bluegill, carp) are common in the Lower Bear Creek Watershed.

The watershed has a diverse assemblage of wildlife habitats and wildlife species that are commonly associated with the vegetation communities discussed earlier. This includes several special-status species. Blacktail deer are the most important big game species, and herd numbers are known to be in decline.

Management Objectives

The Bear Creek Watershed Group (BCWG), together with the Western Shasta RCD, completed the Bear Creek Watershed Assessment in January 2006, and the Bear Creek Watershed Management Strategy in March 2006. The Management Strategy includes a list of objectives for each of the principal management issues (e.g., hydrology and water quality, fisheries, land use, fire and fuels). Management issues and objectives for the Bear Creek Watershed are summarized as:

- establish baseline data, and a continuing monitoring program, for water quality, streamflow, fish population, geomorphic channel conditions, and forest fuels;

- implement management practices that will contribute to improvements in water quality and instream flow;

- identify diversions/barriers for anadromous fish and install screens and ladders for passage;

- expand land conservation practices to preserve open space and protect critical habitat;

- implement fuels reduction and fuelbreak projects to reduce risk of wildfire; and

- establish an education/outreach program to promote good watershed stewardship.

Life in the Watershed

The Bear Creek Watershed is sparsely populated, and land use is predominantly timber production and livestock grazing. Agricultural operations (mostly irrigated pasture) are sustained by surface water diversions and groundwater pumping. The largest community is Shingletown, with a population of approximately 2,500. One of the principal management concerns of watershed residents is possible increase in rural residential development and its impact on open space, country lifestyle, and wildland resources.

Management Organizations Active in the Watershed

Bear Creek Watershed Group

In 2002, a group of residents in the Bear Creek Watershed approached the Western Shasta RCD for assistance in forming a watershed group. The RCD facilitated several community meetings that resulted in the formation of the organization. Grant funding was secured and with the assistance of the RCD, Bear Creek Watershed Group completed a watershed assessment and management strategy. BCWG and the RCD will continue to seek funding support and technical assistance to implement projects targeted to the management issues and objectives identified above.

The “Great Wall of Ash Creek”

"If we had the time, we could build a hundred miles of rock fences" -- Rich Morgan

When a person begins to view the miles and miles of rock fences along Rich Morgan’s ranchlands east of Anderson, two immediate questions jump to mind: First, how long did it take to build the things? And second, how many rocks could possibly be lying around southeastern Shasta County?

Area historian Dottie Smith calls the rock walls the “eighth wonder of Shasta County.” “Any person I take out there on a tour, they’re totally shocked,” Smith says. “They’re so unusual and beautiful.”

Rich Morgan’s wife Maxine, thinks it’s a beautiful legacy that her husband is leaving with the rock walls. Morgan himself says the fences are simply a matter of practicality. “We got tired of chasing cows up and down the road,” says Morgan, who’s been in the cattle business since the 1950s. The rock fences—some 17 miles of them—are impossible to miss along Ash Creek and Wildcat roads. They are 4 to 5 feet tall, and an equally impressive 5 to 6 feet wide.

Morgan and his crews have worked on the walls over the past 9 years, but only during about 2 months of each summer. During the spring and fall, they’re too busy moving and tending to cattle. In the winter, it’s too wet. In addition to containing cattle, the thousands of rocks used for the walls have freed up some of the land, allowing more grass to grow. All the smaller rocks were lifted from the ground by hand and put into a loader. The large base rocks were set in place with the help of an excavator.

The seemingly countless amounts of rocks in the area were left behind from massive mud and ash flows (lahars) from the Lassen Volcanic National Park area after Mount Tehama erupted more than a million years ago, says Bureau of Land Management geologist Ron Rogers. The mudflows are known as the Tuscan Formation.

Even though it looks like a billion rocks have already been used, Morgan says there are plenty more. “If we had the time, we could build a hundred miles of rock fences,” he says.

(From Enjoy Northern CA Living, October 2010)